The Murder of Henri the Elder Project

Introduction

The Murder Ballad of Bishop Henri details the supposed start of Christianity in Finland. The origin of the story has its roots in the twelfth century. The actual ballad appears in the Kanteletar, a collection of Finnish poems and ballads compiled by Elias Lönnrot. It was originally published in 1840 under the name “Kanteletar taikka Suomen Kansan Wanhoja Lauluja ja Wirsiä” (Kanteletar, or Old Songs and Hymns of the Finnish People). The poems and verses that Elias Lönnrot gathered, played an important role in giving definition to the Finnish national identity which later led to Finland becoming an independent state.

Summary

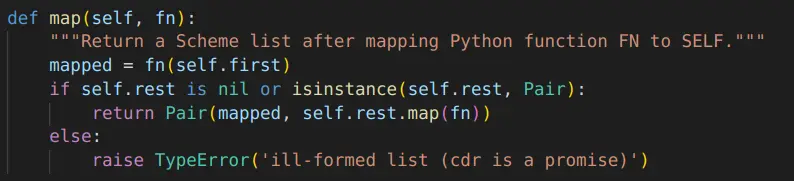

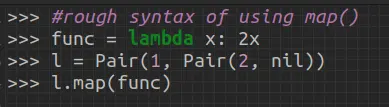

The story begins with two brothers, King Eric of Sweden and Bishop Henri of Häme. Henri suggests to King Eric that they go Christianize the pagan lands of Finland. As Henri is traveling through Finland he becomes hungry and goes to the home of Lalli. Lalli is not there, but his wife, Kerttu, is. Henri takes what he needs from the home and leaves money behind. When Lalli returns home, Kerttu tells him that some people came and stole from them. Enraged, Lalli goes out to kill Bishop Henri.

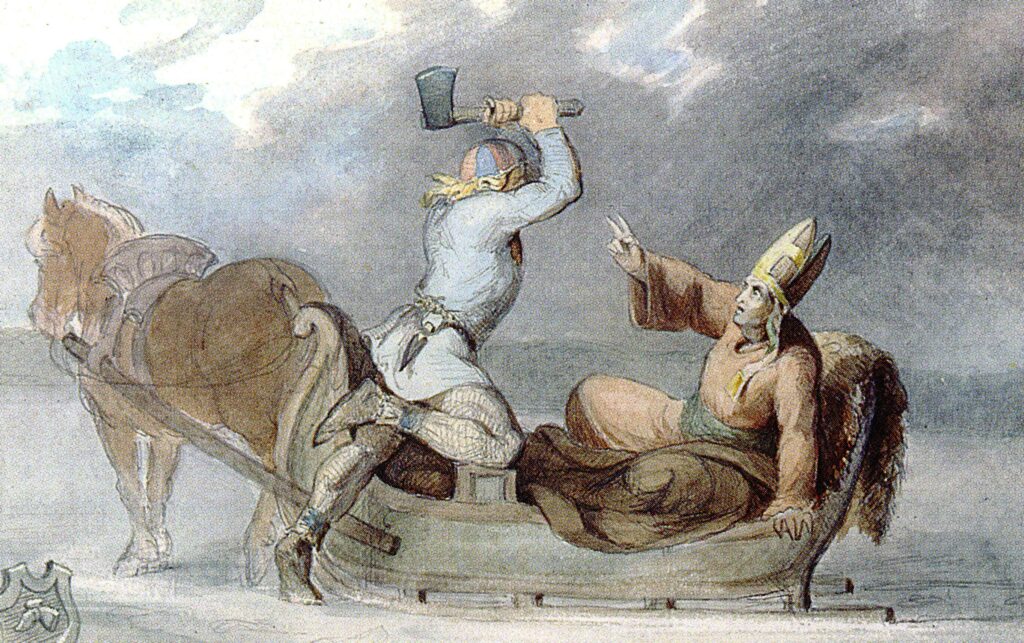

A shepherd and a slave both tell him on the way that his wife lied and he should not kill the Bishop. He ignores them though and eventually catches up to Bishop Henri. Before he dies, Bishop Henri tells his companions, that if he die, to gather his bones in the sled and let the ox take it wherever. Where the Ox eventually tires, there they are to build a church.

After Lalli kills Bishop Henri, he takes his hat and ring. Upon returning home, the shepherd remarks on Lalli’s new ring and hat disapprovingly. Shamefully, Lalli removes the hat and ring. In doing so, he loses tufts of his hair and the ring strips the skin from off his finger. In this way, he receives a punishment from on high for murdering a holy man.

The Ballad

English

Once there grew two children,

one grew up in cabbage land,

the other was raised in Sweden.

The one from cabbage land,

he was Henrik of Häme.

The one raised in Sweden,

he became King Eric.

Henrik of Häme said

to his brother Eric:

“Let us go and baptize lands,

lands that are yet unbaptized,

places without priests!”

King Eric said

to his brother Henrik:

“But the lakes are not yet frozen,

the winding river is still flowing.”

Henrik of Häme said

to his brother Eric:

“I will circle Kiulo Lake,

around the winding river.”

He harnessed his horses,

placed bridles on them,

set the carriages in place,

attached the sled runners,

fitted the wide shoes on,

and the smaller sled planks.

He soon set off driving,

traveled the path, journeyed on,

two spring days,

and two nights in a row.

King Eric said

to his brother Henrik:

“Hunger comes upon us,

and there is neither food nor drink,

nothing to bite or chew.”

“There is Lalli across the bay,

a good place atop the cape

There we will eat and drink

there we find food”

Upon arriving there,

Kerttu, the wicked mistress,

spoke with a vile mouth,

spouted unkind words.

Then Henrik of Häme

took hay for the horses,

threw coins in its stead,

took bread from the oven’s top,

threw coins in its stead,

took beer from the cellar,

and left money in return.

There they ate, there they drank,

there they found sustenance;

then they left to journey onward.

Lalli returned home. –

But Lalli’s wicked wife

spoke with her vile mouth,

spouted unkind words:

“People came here,

ate here, drank here,

found sustenance here,

took hay for the horses,

threw coins in its stead,

ate bread from the oven’s top,

threw coins in its stead,

drank beer from the cellar,

left sand in its stead.”

The shepherd on the hill said:

“You surely have lied;

do not believe her!”

Lalli, the ill-natured one,

a man of wicked lineage,

took his swift horse,

and his long spear,

and chased after the lords.

The loyal slave said,

the faithful worker spoke:

“There’s a rumble behind us;

shall I drive the horse faster?”

Henrik of Häme said:

“If there is a rumble behind us,

do not drive the horse faster;

just keep the pace steady.”

“What if they catch us

or even kill us?”

“Go behind a rock,

listen from behind the rock.

If I am caught

or killed as well,

gather my bones from the snow,

place them in an ox’s sled,

let the ox pull them to Finland.

Wherever the ox tires,

there a church shall be built,

a chapel constructed,

where the priest will preach,

for all the people to hear.”

The wicked one returned home.

The shepherd on the hill said:

“Where did Lalli get that hat,

the evil man with a fine cap,

the bishop’s mitre for a rogue?”

So the man, in his sorrow,

reached for the hat on his head:

his hair fell in tufts.

He removed ring from his finger:

his flesh slipped away.

Thus this ill-natured man,

the wretched slayer of the bishop,

received his punishment from on high,

paid the price to the ruler of the world.

Finnish

Kasvoi ennen kaksi lasta,

toinen kasvoi kaalimaassa,

toinen Ruotsissa yleni.

Se kuin kasvoi kaalimaassa,

se Hämeen Heinrikki,

se kuin Ruotsissa yleni,

se on Eirikki kuningas.

Sanoi Hämeen Heinrikki

Eirikille veljellensä:

”Läkkäs maita ristimähan,

mailla ristimättömillä,

paikoilla papittomilla!”

Sanoi Eirikki kuningas

Heinrikille veljellensä:

”Ent on järvet jäätämättä,

sulana joki kovera.”

Sanoi Hämeen Heinrikki

Eirikille veljellensä:

”Kyllä kierrän Kiulon järven,

ympäri joki koveran.”

Pani varsat valjahisin,

suvikunnat suitsi suuhun,

pani korjat kohallensa,

saatti lastat sarjallensa,

anturoillensa avarat,

perällensä pienet kirjat.

Niin kohta ajohon lähti,

ajoi tietä, matkaeli,

kaksi päiveä keväistä,

kaksi yötä järjestänsä.

Sanoi Eirikki kuningas

Heinrikille veljellensä:

”Jo tässä tulevi nälkä

eikä syöä eikä juoa

eikä purtua pietä.”

”On Lalli lahen takana,

hyvä neuvo niemen päässä,

siinä syömmä, siinä juomma,

siinä purtua piämmä.”

Sitte sinne saatuansa

Kerttu, kelvoton emäntä,

suitsi suuta kunnotonta,

keitti kieltä kelvotonta.

Sitte Hämeen Heinrikki

otti heiniä hevosen,

heitti penningit sijalle,

otti leivän uunin päältä,

heitti penningit sijalle,

otti olutta kellarista,

vieritti rahat sijalle.

Siinä söivät, siinä joivat,

siinä purtua pitivät;

sitte lähtivät ajohon.

Tuli Lalli kotiansa. –

Tuo Lallin paha emäntä

suitsi suuta kunnotonta,

keitti kieltä kelvotonta:

”Jo tässä kävi ihmisiä,

täss’ on syöty, täss’ on juotu,

tässä purtua pietty,

viety heiniä hevosen,

heitty hietoia sijahan,

syöty leivät uunin päältä,

heitty hietoja sijahan,

juotu oluet kellarista,

saatu santoa sijahan.”

Lausui paimen patsahalta:

”Jo vainen valehtelitki,

elä vainen uskokahan!”

Lalli se pahatapainen

sekä mies pahasukuinen,

otti Lalli laukkarinsa,

piru pitkän keihä’änsä,

ajoi herroja taka’an.

Sanoi orja uskollinen,

lausui parka palvelija:

”Jo kuuluu kumu takana,

ajanko tätä hevoista?”

Sanoi Hämeen Heinrikki:

”Jos kuuluu kumu takana,

elä aja tätä hevoista,

karkottele konkaria.”

”Entä jos tavoitetahan

taikkapa tapetahanki?”

”Käy sinä kiven ta’aksi,

kuultele kiven takana,

jos mua tavoitetahan

taikka myös tapetahanki.

Poimi mun luuni lumesta,

ne pane härän rekehen

härän Suomehen veteä.

Kussa härkä uupunevi,

siihen kirkko tehtäköhön,

kappeli rakettakohon,

papin saarnoja sanella,

kansan kaiken kuultavaksi.”

Palasi paha kotia,

lausui paimen patsahalta:

”Kusta Lalli lakin saanut,

mies paha hyvän hytyrän,

pispan hiipan hirtehinen?”

Niinpä mies murehissansa

lakin päästänsä tavoitti:

hivukset himahtelivat.

Veti sormuksen sormesta:

lihat ne liukahtelivat.

Niin tämän pahantapaisen

pispan raukan raatelijan

tuli kosto korkialta,

makso mailman valtialta.

Impact

Bishop Henri has gone on to become the Patron Saint of Finland and an enduring symbol of the Christianization of Finland. Lalli, despite his negative portrayal in the story, has also become a recognized symbol of Finnish resistance to foreign influence. Dozens of offshoot stories and legends surrounding the bishop and Lalli have popped up throughout the last centuries.